The History of Beaufort

County, South Carolina:

1514-1861

By Lawrence Sanders Rowland

Google Books extract

....rumors circulated throughout the province suggesting possible action

against South Carolina, and the local committees were directed to attend to

militia discipline and secure arms and ammunition. The available resources of

public gunpowder became objects of concern. The Council of Safety seized 3,000

pounds of gunpowder in Charleston, and in September 1775 Captain Thomas

Heyward Jr. led the patriot company which crossed Charleston harbor in a

rainstorm to occupy strategic Fort Johnson and commandeer its artillery.

The most feared and most likely threat to South Carolina was

that royal authorities would use their contacts to incite the Cherokee and

Creek Indians to lay waste to the frontier settlements. The Council of Safety

learned in June 1775 that two large shipments of powder were being sent to

Savannah, still controlled by Governor Wright's royal administration, and to

the British garrison at St. Augustine. It was suspected that this powder was

destined for the Indians, and the council promptly dispatched two expeditions

to intercept the ships at sea.

The first expedition, in June of 1775, was led by Captain

John Barnwell Jr. of the Beaufort militia and Captain John Joyner. the Port Royal harbour pilot. With forty men in two barges, they lay in wait at Bloody Point,

Daufuskie Island, where they could command the Savannah River entrance from the

South Carolina side. Governor Wright of Georgia learned of their presence and

dispatched an armed schooner to Tybee Island to counter the Beaufort vessels

and escort the powdership to Savannah. The forces of Barnwell and Joyner.

however, had encouraged the previously weak opposition party in Georgia. Joseph Habersham now assumed the leadership of the patriot cause in Georgia and

with the help of John Joyner secured an armed ship in the Savannah River.

Habersham, Captain Brown, and a body of Georgia patriots bore down on the

British schooner at Tybee Island and chased it out to sea. Just as the British

armed schooner sailed off, the London packet ship Little Carpenter, under the

command of Captain Maitland, arrived off Tybee Island with 16,000 pounds of

gunpowder. Sensing trouble, Maitland tacked about and tried to escape to the

open ocean. The powder ship was overtaken and captured by Habersham's ship from

Savannah and Barnwell and joyners two barges from Beaufort. ”The powder was

divided between the patriot forces of the two colonies. Colonel Stephen Bull,

in command of the militia forces of the Beaufort District, stored a good deal

of the powder in the Prince William Parish Church next to his own Sheldon

plantation. Five thousand pounds of the prize was shipped directly to

Philadelphia at the request of the Continental Congress to eventually find its

way to the artillery of Washington's army currently besieging Boston.20

The second expedition, in July

1775, was commanded by Captain Clement Lempriere of Mount Pleasant, one of

South Carolina's most experienced seamen. The armed sloop Commerce left Port

Royal for St. Augustine sometime.....

Shipyards and European Shipbuilders in

South Carolina

(Late

1600s to 1800)

By Lynn Harris

Occasional Maritime Research

Papers

Maritime Research Division,

South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, USC

As soon as the early Carolina colonists cleared their land and built their

homes, they undoubtedly turned back to the sea and constructed watercraft. The

rivers and creeks of what was to become known as the Carolina Lowcountry

provided ready-made highways for the colonists, and they needed a variety of

watercraft to carry on the business of establishing a new colony. They needed

vessels to visit their neighbors, to trade with the friendly natives who

inhabited the region, to carry goods from a central landing place to their

respective homes, and (not least of all) to explore their new world.

Fortunately, any colonist with the tools and knowledge to build a house could

build a boat to suit almost any purpose.

A Slow Beginning

In a letter written in 1680,

Maurice Mathews, one of the colony's original settlers and eventually its

surveyor-general and Commissioner to the Indians, noted that "Ther[e] have

been severall vessells built here, and there are now 3 or 4 upon the Stocks.” This is perhaps the first written

record of boat building in Carolina and probably refers to "vessells"

capable of at least coastal trading. The myriad amount and variety of small

skiffs, launches, barges, boats, and canoes needed by the colonists would

hardly be worth mentioning.

More evidence of early shipbuilding in the colony comes from the ship

registers. Under English law, vessels used for inter-colonial or trans-oceanic

trading were required to be registered. Few of these records remain. However,

dispersed amongst the colony's early records of deeds, inventories, bills of

sale, and wills are several registers for the year 1698. Of these fifteen

remaining registers, only four are for vessels built in "Carolina.” These

are the 30-ton sloop Ruby and the 50-ton sloop Joseph both built

in 1696, the 30-ton brigantine Sea Flower built in 1697, and the 30-ton

sloop Dorothy & Ann built in 1698.

There are other indications that

the shipbuilding industry in South Carolina got off to a slow start. In 1708, Governor

Nathaniel Johnson reported to the Board of Trade in London that "There are

not above ten or twelve sail of ships or other vessells belonging to this

province about half of which number only were built here besides a ship or

sloop now on the stocks near launching. In 1719, Governor Robert Johnson

reported that "Wee are come to no great matter of [ship]building here for

want of persons who undertake it tho no country in the world is [as]

plentifully supplyed with timber for that purpose and [so] well stored with

convenient rivers . . ." He notes that of the twenty or so vessels

belonging to the port, "some" were built here.

Largest Manufacturing Industry

Occasional Maritime Research

Papers

Maritime Research Division,

South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, USC

As the colony grew and began to

thrive so did the boat and ship building industries.

While not comparable with the

shipbuilding activities of the northern colonies, shipbuilding became South

Carolina's largest manufacturing industry. And just as important, was its

impact on the local economy. In addition to shipwrights, the construction of a

vessel needed the services of joiners, coopers, blacksmiths, timber merchants,

painters, chandlers, glaziers, carvers, plumbers, sailmakers, blockmakers,

caulkers, and oarmakers among others.

The extant ship registers show

that between 1735 and 1775 more than 300 ocean-going and coastal cargo vessels,

ranging from five to 280 tons burthen, were built by South Carolina

shipbuilders. This included ships, snows, brigantines, schooners, and sloops.

These names referred to the vessel's rig, that is its mast and sail

arrangement, and vessels were seldom mentioned without accompanying it with its

type. This preoccupation with a vessel's rig is understandable. Denoting the

rig distinguishes the schooner Betsy, from the brigantine Betsy,

or the sloop Betsy. Even more, those tall wooden masts and billowing

sails of the various rigs were easily its most recognizable feature and the

first part of a vessel that appeared as it approached over the horizon.

Undoubtedly, Carolina-built

vessels were quite similar in most ways to those being built in Britain and the

other colonies. The wide, rounded hull-shape of the oceangoing cargo carrier,

with its blunt bow and tapering stern at the waterline -- meant to imitate the

shape of a duck gliding through water -- and square stern cabin, had become,

like the rigs themselves, fairly standard and widely copied by shipbuilders

after centuries of development, innovation, and imitation. Since many of the

shipwrights of colonial South Carolina were trained in the best English

shipyards or in other parts of America, this is hardly surprising. John Rose,

the Hobcaw shipbuilder, had learned his trade on the Thames at the Deptford

Naval Yard. His partner, James Stewart, had apprenticed at the Woolrich Naval

Yard, also on the Thames, and many of the other prominent Carolina shipbuilders

had learned the art of shipbuilding before arriving in the colony. Georgetown

shipwright Benjamin Darling had come to Carolina from New England. Charles

Minors who built vessels in Little River came from Bermuda, while Robert Watts

who set up his shipbuilding business at the remote Bloody Point on Daufuskie

Island, where he built the 170-ton ship St. Helena in 1766 and the

260-ton ship Friendship in 1771, had come to South Carolina from

Philadelphia. Nevertheless it would be hard to imagine that local shipwrights

and boatbuilders weren't being influenced by local conditions and preferences

and modifying the basic designs so that their vessels accommodated the needs of

their customers.

Ships and Schooners

For evidence of ship design

meeting environmental conditions and customer’s needs,

we turn again to the available

ship registers. They show that the Carolina-built, shiprigged vessel was, in

general, of moderate size, yet larger than ships being built in the

other shipbuilding colonies.

South Carolina shipwrights were certainly able to build large

ocean-going ships. The 280-ton

ship Queen Charlotte, built in 1764 by John Emrie, and the 260-ton ship Atlantic,

built at Port Royal in 1773, are two examples. However, shiprigged vessels

built in South Carolina during this time averaged 180 tons. A ship in the 150-

to 200-ton range seems almost the unanimous choice of Carolina shipowners, with

more than half of those built in South Carolina in that range. While these

ships were of a rather moderate size, Carolina shipwrights turned out ships

that were on the average 40 percent larger than those being produced in other

colonies. From available port records we find that ships built in the other

colonies averaged only about 130 tons burthen.

Perhaps the epitome of the South

Carolina-built ship was the Heart of Oak, built at the Hobcaw yard of

John Rose in 1763. Not only did its180-ton size prove typical of the size of

locally built ships, but the quality of its workmanship would be proven over a

successful career spanning more than 10 years. The Heart of Oak' s

illustrious career began almost immediately after her launching. The S.C. Gazette

for 21 May 1763 reported that "The fine new ship Heart-of-Oak,

commanded by Capt. Henry Gunn, lately built by Mr. John Rose at Hobcaw, came

down (to town) two days ago, completely fitted, and . . . 'tis thought she will

carry 1100 barrels of rice, be very buoyant, and of an easy draught.” An

"easy draught" in 1763 could be considerable. Lloyd's Register for

1764 lists her as having a draught of 14 feet fully loaded. During the colonial

period, it was generally accepted that at low tide only 12 feet of water

covered the deepest channel through the offshore bar, and in 1748, Governor

James Glen noted, "Charles-Town Harbour is fit for all Vessels which do

not exceed fifteen feet draught.” This meant that the Heart of Oak, with

its "easy draught," had to be careful when it crossed the bar fully

loaded. Rose was a passenger on the Heart of Oak' s maiden voyage when

it sailed for Cowes, England on 22 June 1763. He was traveling to England in an

attempt to recruit shipwrights to come to Carolina. There can be little doubt

that he used the Heart of Oak as an example of the excellent

shipbuilding materials and craftsmanship available in Carolina. He returned in

the Heart of Oak in February 1764. His efforts were considered a

failure. In April 1763, when the Heart of Oak was registered, John Rose

listed himself as sole owner; however, by June of 1766 Henry Laurens, who owned

one forth of the ship, valued his one-quarter interest in the Heart of Oak at

£4,000. This sum can perhaps be put into perspective by noting that at the same

time he valued Mepkin Plantation, his 3,000- acre property on the Cooper River,

at £7,000.

One thing is certain - Carolinians preferred schooners. South Carolina

shipwrights built more schooners than all other types of vessels put together.

The ship registers indicate that the two-masted fore-and aft-rigged schooner,

ideal for coastal trading vessels, averaged about 20 tons burthen and accounted

for about 80 percent of the registered South Carolina-built vessels. This appears

somewhat astonishing, especially when compared to records from the other

colonies where the schooner accounted for only about 25 percent of the vessels

built. Elsewhere in the American colonies, the one-masted sloop rig, such as

the remains of the Malcolm Boat appears to be, was the most popular rig,

accounting for roughly one-third of all vessels registered in the colonies.

This penchant for schooners is

perhaps a result of the coastal trade that formed a large part of the commerce

in and out of Charleston. In addition to a lively Atlantic and Caribbean trade,

Carolinians carried on an extensive and active coastal trade. Rice, indigo,

lumber, naval stores, and the other products of the coastal plantations and

settlements had to be transported to Charleston for trans-shipment to England

and elsewhere. And, the products from England and Europe that arrived in

Charleston had to be distributed back to these colonists who were starved for

manufactured goods of all kinds. This coastal trade required a small, fast,

shallow-draft vessel that was maneuverable enough to sail amongst the coast's

sea island. The small coasting schooner being built by Carolina shipbuilders

fit the bill perfectly. Looking at the records of port arrivals and departures

for a one year period from June 1765 to June 1766, we find the majority of

cruises for schooners involved short coastal runs while sloops were being used

for short ocean cruises, such as those to the Caribbean and Bermuda.

Shipyards and Shipwrights

As the colonists spread out along the waterways so did the shipbuilding

efforts. The registers list construction sites along most of South Carolina's

rivers -- at places such as Pon Pon, Dorchester, Bull's Island, Dewees Island,

Wadmalaw, Combahee, and Pocotaligo. But the major shipbuilding areas centered

around Charleston, Beaufort, and Georgetown.

Most shipbuilding in Charleston

took place outside the city proper. The three areas near town that became

shipbuilding centers were James Island, Shipyard Creek, and Hobcaw. Although no

shipyard sites have been located on James Island, the colonial ship registers

indicate a good amount of shipbuilding on the island. Between 1735 and 1772,

more than thirty vessels list James Island as their place of construction in

the ship registers. This includes the 130-ton ship Charming Nancy, built

in 1752 for Charleston merchants Thomas Smith Sr. and Benjamin Smith. Shipyard

Creek, now part of the naval base near Charleston, was another shipbuilding

site during the colonial period (Smith 1988: 50). Many of the ships listing

Charleston as their place of construction in the ship registers were probably

built on Shipyard Creek.

During the last half of the

Eighteenth century, Hobcaw Creek off the Wando River became the colony's

largest shipbuilding center, boasting as many as three commercial shipyards in

the immediate vicinity. The largest shipyard in the Hobcaw area, indeed in all

of colonial South Carolina, was the one started on the south side of the creek

in 1753 by Scottish shipwrights John Rose and James Stewart.

After making a considerable

fortune, Rose sold the yard in 1769 to two other Scottish shipwrights, William

Begbie and Daniel Manson. In 1778, Paul Pritchard bought the property and

changed its name to Pritchard's Shipyard. During the Revolution, the South

Carolina Navy Board bought control of the yard and used it to refit vessels of

the South Carolina Navy. After the Revolution, ownership of the yard reverted

to Pritchard, and the property stayed in the Pritchard family until 1831.

Another shipwright who owned a

yard in the vicinity of Hobcaw Creek during South Carolina's colonial period

was Capt. Clement Lempriere. The exact location of his yard is unknown, but in

all likelihood, it was near or at Remly Point. A 1786 plat of the Hobcaw Creek

area reveals the site of the shipyard of David Linn located on the north side

of the creek. Linn had been a shipbuilder in Charleston as early as 1744 and

purchased the Hobcaw property in 1759.

Georgetown and Beaufort also

developed shipbuilding industries during the colonial period. The South

Carolina ship registers indicate Georgetown had a thriving shipbuilding

industry from 1740 to about 1760. More than 30 vessels list Georgetown as the

site of construction during this period including the 180-ton ship Francis,

built in 1751. Benjamin Darling probably built the Francis since his was

the largest shipyard in Georgetown during this period.

The South Carolina Gazette for

28 September 1765 notes that "within a month past, no less than three

scooners [sic] have been launch'd at and near the town of Beaufort, one built

by Mr. Watts, one by Mr. Stone, and one by Mr. Lawrence; besides which, a pink

stern ship, built by Mr. Black, will be ready to launch there next Monday, and

very soon after, another schooner, built by Mr. Taylor, one by Mr. Miller, and

one by Mr. Toping; there is also on the stocks, and in great forwardness, a

ship of three hundred tons, building by Mr. Emrie; and the following contracted

for, to be built at the same place, viz, a ship of 250 tons, and a large schooner,

by Mr. Black; another large ship and a schooner by Mr. Watts; two large schooners,

by Mr. Lawrence, and on by Mr. Stone." The ship registers verify this

abundance of shipbuilding and indicate a proliferation of construction activity

between 1765 and 1774.

It would be wrong to assume that

all this shipbuilding was taking place at large commercial shipyards. Shipyards

during this period ranged from the well-established yard such as John Rose's on

Hobcaw which employed perhaps 20 persons building large ships to the

"shade tree" variety were one or two persons built small sloops and

schooners without any help and worked elsewhere between construction jobs. And

this doesn't include the handyman who built a canoe or small sailing skiff for

his own personal use. While specific records concerning small boat building do

not exist, the newspapers of the time are filled with advertisements indicating

a wide variety of locally made watercraft for sale. These small craft virtually

littered the local waterways. In 1751, Governor James Glen noted that "Cooper River appears sometimes a kind of floating market, and we have numbers of canoes,

boats and pettiaguas that ply incessantly, bringing down the country produce to

town, and returning with such necessary as are wanted by the planters".

Live Oak, Yellow Pine, and

Long Life

The early boatbuilders as well

as shipwrights found local woods excellent building materials. The massive,

naturally-curved live oak for the vessel's main timbers, and the tall, yellow

pines and for planking and decking were as ideally suited for the small skiff

as for the large three-masted ship. The Gazette for 28 September 1765,

after noting the vessels presently being built by Carolina shipwrights, claims

that "as soon as the superiority of our Live-Oak Timber and Yellow Pine

Plank, to the timber and plank of the Northern colonies, becomes more generally

known, 'tis not to be doubted, that this province may vie with any of them in

that valuable branch of business . . ." And, six years later, the Gazette

for 8 August 1771 reports that there had been several recent orders for

Carolina-built ships from England as "Proof that the Goodness of Vessels

built here, and the superior Quality of our Live-Oak Timber to any Wood in America

for Ship-Building, is at length acknowledged." Of course, the Gazette's

enthusiasm may have been somewhat of an eighteenth century public relations

effort, but there were others with no, or at least less visible, ulterior

motives who praised Carolina-built vessels.

Henry Laurens, the owner of many

vessels built both in South Carolina and elsewhere, was one who promoted the

superiority of the Carolina vessels and the skill of local shipwrights. In 1765

while discussing the cost of shipbuilding in Carolina with William Fisher, a

Philadelphia shipowner, he notes, "The difference in the Cost of our

Carolina built Vessels is not the great objection to building here. That is

made up in the different qualities of the Vessels when built or some people think

so.” He adds that a vessel built in Philadelphia "would not be worth half

as much (the hull of her) as one built of our Live Oak & Pine . . .”

Writing to his brother James from England in 1774 in reference to acting as an

agent in having a ship made in Carolina for a Bristol mercantile firm, he

admits his hope that a Carolina-built ship on the Thames would assure that

"our Ships built of Live Oak & Pine will acquire the Character &

Credit which they truly Merit." Live oak and pine construction, along with

the other popular shipbuilding timbers, were frequent advertising points in a

vessel's sale. On 21 May1754, the South Carolina Gazette ran a typical

ad of this sort. It was for the sale of a schooner that would carry 95 to 100

barrels of rice. The ad notes that the vessel is "extraordinary well

built, live oak and red cedar timber, with two streaks of white oak plank under

her bends, the rest yellow pine.” Live oak was an obvious and common choice for

shipbuilding, yet cedar, although immensely less abundant, was also a favorite

shipbuilding material due to its ability to resist the infamous teredo worm,

also known as the shipworm. In 1779 when the new state sought to have a 42-foot

pilot boat made the specifications recommended "the whole of the frame Except

the flore [floor] Timbers be of Ceadar."

These woods also made for

vessels with long lives. At a time when the average life expectancy of a wooden

vessel was about fifteen years, Carolina-built ships boasted usual lives of

twenty to thirty years. In 1766, the 20-ton schooner Queenley was

registered to trade between Carolina and Georgia. The Queenley was built

in 1739 in South Carolina, twenty-seven years earlier. When the 15-ton schooner

Friendship was registered for trade in 1773, it was already twenty-eight

years old, having been built at Hobcaw in 1745. The South Carolina Gazette ran

a story in 1773 that the aptly named 125-ton ship, Live Oak, was

"constantly employed in the Trade between this Port and Europe." The Live

Oak had been built on James Island twenty-four years earlier. This quality

of Southern timber even reached the ears of Alexander Hamilton who wrote in his

Federalist Papers "The difference in the duration of the ships of which

the navy might be composed, if chiefly constructed of Southern wood, would be

of signal importance . . . "

USS John Adams

The high point of South Carolina

wooden shipbuilding occurred on 5 June 1799 with the launching of the 550-ton

frigate John Adams at the Paul Pritchard Shipyard on Shipyard Creek. The

John Adams carried twenty-six 12-pound cannons and six 24-pound

carronades making her the first U.S. Navy vessel to be armed with carronades.

She was built with a variety of native South Carolina woods. The floor timbers

and futtocks were of live oak. The upper timbers were of cedar. The keel and

keelson were of Carolina pine while the masts and spars were of long-leaf pine.

The deck beams were hewn from yellow pine logs cut along the Edisto River. In

1803, she saw action off Tripoli against the Barbary Powers. During the War of

1812, she spent most of her time blockaded in New York harbor. In 1863, at the

age of sixty-four, she was ordered to join the South Atlantic Blockading

Squadron off South Carolina. Her long and illustrious career ended in 1867 when

she was sold out of the Navy and sent to the breaker's yard.

Decline of Wooden Ships

The wooden shipbuilding industry

declined during the first half of the nineteenth century. This was due to a

general economic decline in the state and, of course, the development of steamships

and steel-hulled vessels. However, small wooden vessels -- yachts, fishing

boats, pilot boats, barges, canoes, skiffs, launches, dugouts, batteaux, etc. -

- were still being constructed and used on the river and coastal waterways of

this state.

This small boat industry

continued into the twentieth century.

References

Albion, Robert Greenhalgh. 1926 Forests

And Sea Power: The Timber Problem of The Royal Navy 1652-1862.

Cambridge: Harvard University

Press.

Charleston County Probate Court

Records (CCPCR),

Wills and Miscellaneous Records,

Vol. 54 (1694-1704).

Charleston County Register of Mesne Conveyance Records (CCRMCR).

Coker, P. C., III

1987 Charleston's Maritime

Heritage, 1670-1865. Charleston: CokerCraft Press. Crowse, Converse D.

1984 "Shipowning and

Shipbuilding in Colonial South Carolina: An Overview.” The American Neptune 44,

no 4 (Fall 1984): 221-244.

Dunne, W.M.P.

1987 "The South Carolina

Frigate: A History of the U.S. Ship John Adams." The American Neptune 47,

no. 1 (Winter 1987): 22-32.

Fleetwood, Rusty.

1982 Tidecraft: The boats of

lower South Carolina & Georgia. Savannah, Ga.: Coastal Heritage

Society.

Fraser, Walter J., Jr.

1976 Patriots, Pistols and

Petticoats. Charleston: Charleston County Bicentennial Committee.

Goldenberg, Joseph A.

1976 Shipbuilding in Colonial

America. Charlottesville, Va.: The University Press of Virginia. Hamilton,

Alexander.

1941 "Federalist Papers,

No. 11." The Federalist. New York The Modern Library. Labaree,

Leonard Woods.

1967 Royal Instructions to

British Colonial Governors, 1670 - 1776. New York: Octagon Books.

Laurens, Henry

1970The Papers of Henry

Laurens, Volume Two: Nov. 1, 1765 - Dec. 31,1758. Edited by Philip M. Hamer

and George C. Rogers Jr. Columbia: USC Press.

1972 The Papers of Henry

Laurens, Volume Three: Jan. 1, 1759 - Aug. 31, 1763. Edited by Philip M.

Hamer and George C. Rogers Jr. Columbia: USC Press.

1974 The Papers of Henry

Laurens, Volume Four: Sept. 1, 1763 - Aug. 31,1765. Edited by George C.

Rogers Jr. Columbia: USC Press.

1978 The Papers of Henry

Laurens, Volume Six: Aug. 1, 1768 - July 31,1769. Edited by George C.

Rogers Jr. and David R. Chesnutt. Columbia: USC Press.

1979 The Papers of Henry

Laurens, Volume Seven: Aug. 1, 1769 - Oct. 9, 1771. Edited

by George C. Rogers Jr. and

David R. Chesnutt. Columbia: USC Press.

1981 The Papers of Henry

Laurens, Volume Nine: April 19, 1773 - Dec. 12, 1774. Edited by George C.

Rogers Jr. and David R. Chesnutt. Columbia: USC Press.

Lloyd's Register of Shipping 1764

London: Reprinted by The Gregg Press Ltd.

Mathews, Maurice.

1954 "A Contemporary View

of Carolina in 1680." South Carolina Historical Magazine 55, no. 3

(July 1954): 153-159.

Merrens, H. Roy, ed.

1977 The Colonial South

Carolina Scene - Contemporary Views, 1697-1774. Columbia: USC Press.

Milling, Chapman J., ed.

1951 Colonial South Carolina:

Two Contemporary Descriptions by Governor James Glen

and Doctor George Milligen Johnston. Columbia: USC Press.

Olsberg, Nicholas.

1973 "Ship Registers in the

South Carolina Archives, 1734 - 1780." South Carolina Historical and

Genealogical Magazine 74, no. 4 (October 1973): 189-299. Rogers, George C.,

Jr.

1970 The History of

Georgetown County, South Carolina. Columbia: USC Press.

1980 Charleston in the

Age of the Pinckneys. Columbia: USC Press. Salley, A.S., Jr.

1912 Journal of the

Commissioners of the Navy of South Carolina, October 9, 1776 -March 1,

1779. Columbia: The Historical Commission of South Carolina.

1913 Journal of the

Commissioners of the Navy of South Carolina, July 22, 1779 – March 23,

1780. Columbia: The Historical Commission of South Carolina. Smelser, Marhsall,

and William I. Davisson.

1973 "The Longevity of

Colonial Ships." The American Neptune 33, no. 1 (January 1973): 17-19.

Smith, H.A.M.

1988 Rivers and Regions of

Early South Carolina. Spartanburg: The Reprint Co. South Carolina

Gazette Various editions, Uhlendorf, Bernard A., trans. and ed.

1938 The Siege of Charleston.

Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Weir, Robert M.

1983 Colonial South Carolina. Millwood, N.Y.: KTO Press.

The following is from internet Newspaper Archives containing reports of Francis

Maitland 2’s ships:

Lloyds Register

Founded to inspect and examine the physical structure and equipment of merchant

vessels, Lloyd's graded ship hulls on a lettered scale (A being the top), and

ship's fittings (masts, rigging, and other equipment) was graded by number (1

being the top). Thus the top classification was "A1", from which the

expression A1, or A1 at Lloyd's, is derived, first appeared in the 1775–76

edition of the Register. Ship surveyors (usually master mariners or master

shipwrights) conducted surveys of ships calling at British ports

Not all ships were surveyed and included in the Register. From 1834–37, an

attempt was made to include all British vessels of 50 tons or over, although

very little information is given about those which had not been surveyed - in

contrast the Mercantile Navy List records British registered vessels over one

quarter of a ton.

From 1838–1875, only vessels which had been surveyed were included in the

Register. After that date, the Register was extended to take in all British

vessels over 100 tons, and from 1890 its scope was broadened to include all

British and foreign sea-going vessels over 100 tons. It is always possible to

determine whether or not a ship had been surveyed from the entry in Lloyd’s

Register of Shipping, as the resultant Lloyd’s register classification will be

given.

A vessel remains in the Register until something happens to her; for example if

she is sunk, wrecked, broken up, hulked, scrapped, etc.

From 1834 onwards Lloyd’s Register was published mid-year and covered the

period 1 July–30 June the following year. To reflect this, volumes published

after 1868 started to give both years, e.g. 1869–1870.

The following incomplete sequence of 18th & 19th Century volumes were

scanned by Google. They have the advantage of being searchable and so it is

possible to look for masters, owners etc. Please note however names may be

abbreviated, Tmknsn instead of Tomkinson for instance. The 1930-1945 volumes

were scanned by staff at Southampton Library & Archive.

1764-66 1768 1780 1789 1796 1797 1798 1799

1800 1801 1802 1803 1804 1805 1806 1807 1808 1809

1810 1811 1812 1813 1814 1815 1816 1817 1818 1819 1820 1821 1822

1823 1824 1825 1826 1827 1828 1829 1830 1831 1832 1833 1834 1835

1836 1837 1838 1839 1840 1841 1842 1843 1844 1845 1846 1847 1848

1849 1850 1851 1852 1853 1854 1855 1856 1857 1858 1859 1860 1861

1862 1863 1864 1865 1866 1867 1868 1869 1870 1871 1872 1873 1874

1875 1876 1877 1878 1879 1880 1881 1882 1883 1884 1885 1886 1887

1888 1889 1890 1891 1892 1893 1894 1895 1896 1897 1898 1899*

1930-1945

*Incorrectly scanned in reverse, last page first.

N.B. copyright of all images of the 1764-6 edition remain

with Lloyd’s Register. Images © Lloyd’s Register Group Limited 2012

Please see Infosheet no.10 for further details on the

contents of the Lloyd’s Register of Ships, and Infosheet no.44 to help guide

your research when using it. Other collections of the Lloyd’s Register of Ships

in the UK are listed on Infosheet no.17 and collections on Europe can be found

on Infosheet no.46.

Lloyd’s Lists:

http://www.maritimearchives.co.uk/lloyds-list.html

Google have digitised early editions of Lloyd's List . This collection does not

include any issues for 1742, 1743, 1745, 1746, 1754, 1756, 1759 or 1778.

Various issues are also missing from certain volumes. In addition issues up to

1752 are dated using the Julian calendar meaning that the New Year begins on

25th March. The first surviving issue here is dated 2 January 1740 but in the

year we would now think of as being 1741.

The volumes listed here are searchable making it particularly useful for

searching for voyages of particular vessels and the names of masters.

The Marine News section has also been indexed by volunteers at the Guildhall

Library which may help with searching through the volumes listed here.

A series of indexes, covering ship movements and casualties 1838 to October

1927, are on microfilm at the National Maritime Museum, the Guildhall Library,

Merseyside Maritime Museum and the National Library of Scotland.

The National Maritime Museum has also published a brief history of Lloyd's

List.

1741-1744 1747-1748 1749-1750 1751-1752

1753-1755 1757-1758 1760-1761 1762-1763

1764-1765 1766-1767 1768-1769 1770-1771

1772-1773 1774-1775 1776-1777 1779-1780

1781-1782 1783-1784 1785-1786 1787-1788

1789-1790 1791-1792 1793-1794 1795-1796

1797-1798 1799-1800 1801-1802 1803-1804

1805-1806 1807-1808 1809-1810 1811-1812

1813-1814 1815-1816 1817-1818 1819 – 1820

1821 -1822 1823 -1824 1825 - 1826

Achilles: Lloyd’s Register 1764-66 starts at Albemarle – assumed that first

part missing. 1768: A-L missing.

Adventure: as for Achilles; probably not our family, operating out of Leith.

Maitlands searched for 1837,8,9,40 a number of ships sailing from Aberdeen

& Peterhead with masters &/or owners Maitland, but probably not ours

The following is a possibility, but unlikely as sailing from Leith:

1840: Sarah Jane, Bg vnCa, Maitland, 216 (236), N Brns BRRP, 1828?, & Lik,

Dewar & Co, Jamaic, Lth. Jamaica, 4 A1 2-41

1841:

http://www.shipsnostalgia.com/archive/index.php?t-9325.html

Ships Nostalgia > Lost Contact & Research > Ship Research >

Bencoolen

This is a long forum with extracts from the Bencoolen logs between Calcutta

& England via St Helena in July to September, 1841. Westbrook is mentioned

as sailing in the same direction, and doing better than the Bencoolen (a 465

tin ship rigged vessel). Unfortunately, the extracts do not contain dates.

This voyage is the one arriving in Cork in September 1841 from Canton with tea.

Maitland – Brig

http://www.irishshipwrecks.com/shipwrecks.php?wreck_ref=481

|

Name

|

Nationality

|

Location

|

Date Lost

|

|

Maitland

|

British

|

Off Cape Clear Co Cork

|

13/03/1867

|

|

|

|

Maitland :

|

|

Owner

|

Chas.John Brightman, 15 Great St Helens, London

|

|

Flag

|

British

|

Builder

|

Built at Sunderland

|

|

Port

|

Shields

|

Build Date

|

1851

|

|

Official No

|

23354

|

Material

|

Wood

|

|

Lloyds Register

|

|

Tonnage Net/Gross

|

301

|

|

Launched

|

|

Dimensions in ft

|

105.2 | 26.4 | 17

|

|

Ship Type

|

Sail Vessel

|

Rigging Style

|

Snow Brig

|

|

Ships Role

|

Cargo Vessel

|

Funnels

|

|

|

Engine

|

|

|

|

Super Structure

|

|

|

|

Owner and Registration History

|

|

Lloyds Register 1852 Owner J.Kelso Reg N,Shilds

Lloyds Register 1863 Owner Watts And Co Reg N,Shilds

MNL 1867 Owner, Chas.John Brightman.

|

|

|

|

Location

|

75 Miles South West Off Cape Clear Co Cork

|

|

Date Lost

|

13/03/1867

|

Captain

|

|

|

Cause

|

Abandoned

|

Crew Lost

|

|

|

Position

|

|

Passengers Lost

|

|

|

Google Map Location

|

|

|

|

|

|

History

|

|

On the 13th March, when in lat 50.30 N., long 11.30 W., the

master of the brig "Maitland," finding his ship in a sinking state

made signals of distress to the "Lady Love," which came and

remained by her all night. The next morning the master and crew of the

"Maitland," 15 in all proceeded in their own boat on board the

"Lady Love," and were landed at Queenstown on 28th March.

Board

Of Trade Wreck Reports 1867

|

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/673391

The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW)

Wednesday 25 February 1852

20.-Maitland, ship, 648 tons, Captain Henry, from the Downs November 9.

Passengers

Captain A. Vyner, wife, son, and daughter, Mr. E. B. Hamel,

wife and daughter, Mr. M'Gregor, Mrs. Dawson and sou, R. Yule and wife, C.

Graves and wife, J. Guzzaroni, P. Griffiths, W. Armstrong, R. Kingsford and

wife, E. Beasley and wife, R. Kirkpatrick, E. Simkins, T. Boyd, R. Kenyon, T.

Hilson and wife, S. Barton, J. Smith, W. Lewis, H. Wilson, K. Längster, F.

Roberts, T. Audley, E. Butler, H. Chilwell, W. Addison and wife, H. Green, W.

Edwards, W. Trewolla, J. Bevan, G. Wright, G. Penny, G. Inglis, J. Harvey, R.

Young, W. Atkins, J. Coleman, R. Alexander, W. Stranger, G. Farmer and wife, A.

Dubordone, J. Guese, W. Bishop, A. and H. Bradford, W. Hill, C. Seameret, Read,

Smith, White, and Newcombe.

Bute

An East Indiaman, appearing in Lloyds List with Captain Maitland, launched at

Blackwall, 3/2/1763, 670 tons.

http://www.euromodel-ship.com/files/Chronicle-of-the-Black-wall-Yard.pdf

Bute:

not in Lloyd’s Register 1764, 1768 A-L missing, not found 1780.

The Downs

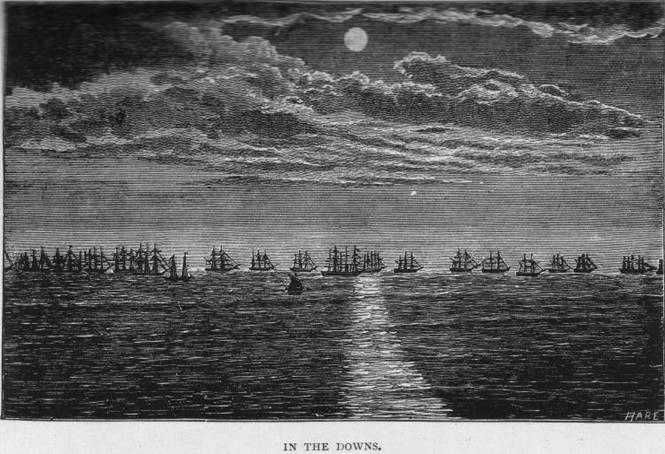

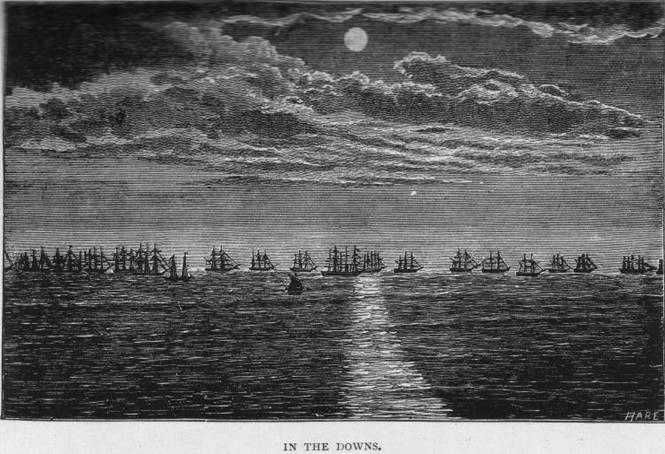

The Downs are a roadstead or area of sea in the southern North Sea near the

English Channel off the east Kent coast, between the North and the South

Foreland in southern England. In 1639 the Battle of the Downs took place here,

when the Dutch navy destroyed a Spanish fleet which had sought refuge in

neutral English waters. From Elizabethan times, the presence of Downs helped to

make Deal one of the premier ports in England, and in the 19th century, it was

equipped with its own telegraph and timeball tower to enable ships to set their

marine chronometers.

The anchorage has depths down to 12 fathoms (22 m).[1] Even during southerly

gales some shelter was afforded, though under this condition wrecks were not

infrequent. Storms from any direction could also drive ships onto the shore or

onto the sands, which—in spite of providing the sheltered water—were constantly

shifting, and not always adequately marked. The Downs served in the age of sail

as a permanent base for warships patrolling the North Sea[2] and a gathering

point for refitted or newly built ships coming out of Chatham Dockyard, such as

HMS Bellerophon, and formed a safe anchorage during heavy weather, protected on

the east by the Goodwin Sands and on the north and west by the coast. The Downs

also lie between the Strait of Dover and the Thames Estuary, so both merchant

ships awaiting an easterly wind to take them into the English Channel and those

going up to London gathered there, often for quite long periods. According to

the Deal Maritime Museum and other sources, there are records of as many as 800

sailing ships at anchor at one time.[3] (Wiki)

"Flat calm in the Downs. The Deal boatmen sometimes call it a 'sheet'

calm. At any rate it is as calm as a pond, but not as motionless, for there is

ever, and ever present the deep breathing of the sea, and always there sweeps

through the Downs the mighty current of the tide - but to use another simile, the

surface is like glass." (Treanor)

The Downs are an anchorage of deep water, open to the north and south,

protected towards the east by the Goodwin Sands, and towards the west by the

mainland. Rev. Treanor described them thus:

"In westerly winds the Downs are full of shipping outward bound, and

waiting for a fair wind. Then on a dark night the long line of their gleaming

riding lights suggests to the spectator some great city in the sea."

"In easterly winds the seaward-going host departs, and there come from the

south and west the homeward-bound clippers, some in tow of steam-tugs for

London, and others bound to northern ports, furling their sails for anchoring

in the Downs till winds from the west and south spring up to bring them to

their voyage end.

The larger vessels anchor in the southern part of the Downs, in eight or ten

fathoms of water, the bottom being chalk; while the smaller vessels bring up

more towards the north, in the Little Downs, in from four to six fathoms of

water, in splendid holding-ground of blue clay. Once an anchor gets into this

blue clay, it will hold the vessel unless her chain-cable parts, or till she

splits her hawse-pipes."

Rev. Treanor speaks of "500 merchant sailing-vessels far-reaching to the

north and south, some homeward, but the great majority of them outward bound to

all parts of the world", of which at least half are British and the

remainder "foreigners of all the maritime nations."

"Whether British or foreign, this host of 500 vessels contains about 5,00

men. For days, and sometimes weeks, they ride at anchor in the Downs, wearied by baffling calms or tempests .."

Even today, when storms threaten, many ships head for the Downs to take shelter

and ride out the weather until it is safe to proceed to harbour. The layout of

the harbour entrances at Dover make it dangerous to attempt an entry when the

wind is blowing in the wrong direction, so it is common in rough weather to see

several vessels, including cross-channel ferries laden with cars and

passengers, riding out the storm off Deal, sometimes for several hours.

".. and at last the sky clears in the north-east, and a golden haze

enshrouds the fleet which on the waves lies heaving many a mile."

".. on every ship the windlasses are manned. You hear the clicks of the

palls as the anchors come up, and the creaking of the yards as they are being

hoisted, and the singing of the sailors as they walk the capstan bars round, or

heave the windlass handles to the strange weird mournful chorus of -

Give a man time

To roll a man down.

Give a man time

To roll a man down."

"And then the sailors nimbly run aloft to loose the sails. The gaskets

are cast off, the bunt lines are let go, the clew lines hauled, and the great

foretopsail bellies out before the freshening north-easter. Each ship spreads

her wings, and they 'fly as a cloud and as the doves to their windows',

presenting a wondrous spectacle of beauty from Deal Beach".[1]

http://www.gleaden.plus.com/landmarks/keppel.htm

Clipper Maitland

Tea clipper built in 1865 by William Pile, Sunderland. Dimensions:

183'0"×35'0"×19'5" and tonnage: 798,72 NRT and 754,58 tons under

deck. Longitudinal section, deck plan and sail plan are preserved in the

Science Museum, London. The builder's half model is in the possession of Joseph

L. Thompson & Sons, Sunderland.

1865 December 2

Launched at the shipyard of William Pile, Sunderland, for John R. Kelso, North

Shields.

1866

Sailed from Sunderland to Hong Kong in 87 days.

1866 July 11 - October 23

Sailed from Foochow to London in 104 days. Captain Coulson.

1867 June 1 - September 24

Sailed from Foochow to London in 115 days.

1867 November 5 - February 16

Sailed from London to Shanghai in 103 days.

1868 October 8 - January 25

Sailed from Shanghai to London in 109 days. Captain Coulson.

1869 July 29 - November 8

Sailed from Hong Kong to London in 102 days. Captain Coulson.

1870 September 10 - December 30

Sailed from Foochow to London in 111 days. Captain Hunter.

1871 February 12 - May 19

Sailed from Cardiff to Hong Kong in 96 days.

1871 July 8 - November 8

Sailed from Foochow to London in 123 days. Captain Reid.

1872 July 19 - November 6

Sailed from Foochow to London in 110 days. Captain Reid.

1873 July 10 - November 3

Sailed from Foochow to London in 116 days. Captain Reid.

1874 May 25

Wrecked on a coral reef in the Huon Islands, New Caledonia, on voyage from

Brisbane to Foochow.

Updated 1996-12-28 by Lars.Bruzelius@udac.se

The Maritime

History Virtual Archives | Ships | Teaclippers

The Maritime

History Virtual Archives | Ships | Teaclippers

Copyright © 1996 Lars Bruzelius. _

Richard Maitland’s Convoy in Duke, March

1757

PRO ADM 1/235, Admiral's

despatches, Jamaica 1713-1789,

1757-1760 Lists and Indexes, Admiralty XVIII p3.

Copied by AM 22/5/2008: jpg files under family images/Maitland.

Marlborough at Spithead, 7th March 1757.

Sir,

I received their Lordships orders of the 5th Instant this morning,

too late to answer by the Post. The two Assistant Surgeons I have ordered on

board the Lynn.

Mr Jones Agent for the Hospital at Haslar applied to me this afternoon to take

on board the Medicines and Stores for the Hospital at Jamaica and at the same

time acquainted me they filled four wagons, it being impossible for me to

receive such a Quantity either in my own Ship or Lynn with the Provisions

ordered by their Lordships. I advised him to ship them on board some Merchant

Ship bound to Jamaica. The Wind is now Eastward of the N and the Convoy from

the Downs all at an anchor, though few of the Masters have yet been on board to

take orders. I propose sailing tomorrow morning, and give them orders at Sea

rather than lose an Opportunity of this Wind.

Inclosed is a List of the Ships under my Convoy, a more exact account of them

will be sent you by the first Opportunity.

I am Sir

Your most Obedient Servant

Thos Cotes

Ships listed with:

Ships Name, Master’s Name, What Built, Were Belonging, Number of Men, Guns,

Tons, From Whence, Whither Bound lading, When Received Order.

An extract:

Duke, Rich’d Maitland, Ship, London, 20, 10, 360, London, Virginia, Ballast, 7th

March 1757. (from NA photograph)

Marlborough at Spithead 10th March 1757.

Sir,

The 8th Instant in the morning I made the Signall to unmoor, and

intended sailing but before I could get my Best Bower Anchor up, the Wind

veered to the Southward and from thence to the Westward, which obliged to moor

again in the Evening, it has since been variable with Calms, but I hope is now

fixed Easterly. I made the Signal to unmoor this morning by break of day and I

hope to get the Convoy out to Sea before Night.

Inclosed is a List of Ships who have taken my orders since my Letter of the 7th

Instant.

I am, Sir,

Your most Obdt Servant,

Thos Cotes

The Wind at NNE with Snow.

Marlborough in Torbay 15th March 1757.

Since my Letter of the 12th Instant from this Place His Majesty’s

Ships Newcastle, Lynn and Hornett have joined me and brought in with them the

merchant ships that were in the rear of the Fleet. The 13th in the

Evening the Wind came to the Northward and I was in hopes of its coming to the

Eastward, I immediately made the Signal for getting ready to sail but before we

could get a Peak on our anchor, it backed to the Westward and began to blow,

and all yesterday it blew very hard at NW and WNW. Last night it was moderate

Weather, and this morning it blows very hard at West.

I have wrote to Rear Admiral Harrison at Plymouth to desire a Supply of Beer

only to be sent here, if the Wind should continue Westerly and keep us here.

I shall sail as soon as the Wind shifts so that I can get down Channell.

Inclosed is the State of His Majesty’s Ships under my Command.

I am Sir,

Your most Obedient Servant,

Thos Cotes.

Marlborough in Torbay 16th March 1757 at 1,0’clock pm

Sir,

The hard gale from the West to NNW that has blown for two days past, ceased

this morning, and at 8 the Wind shifted to No when I made the Signal to prepare

to sail, that the merchant ships might get up their Yards and Topmasts, and

take up one anchor, most of them being obliged to let go two anchors, when it

blew so hard; the Wind now appears to me settled at NNE and I am getting under

sail, that the Fleet may have time to get one before Night,

I am, Sir,

etc.

Marlborough at Sea 8th April 1757.

Latt in 41d 05m N Long 13:35 Wt

Start (Point?) No 38:45 E Dist 230Lg

Finister N54.15E Dist 73 Lgs.

The 17th of March we sailed from Torbay the Wind then blowing fresh

at NNE; by night all the Fleet were got clear; and at 8 we took our Departure

from the Start, the Wind continued Easterly till the 18th, when it

veered to the Westward, and the 20th it blew so hard we could carry

no Sail, and were obliged to bring too under a Mainsail; the Merchant Ships who

did not take care to bear down lost Company, as we drove much faster than them;

The 24th in the Lattitude of 48˚22’ Longitude 5˚ 4’ from

the Start. A Merchant Ship acquainted me, that His Majesty’s Sloop Stork had in

the late bad Weather in the Night carried away all her Masts, but had got up

Jury Masts and was bore away for the Channell, and as the Wind was then at WSW

I hope she soon got into some port. We had very bad weather for fifteen Days

together in the Bay of Biscay, but have now a good Prospect of making our

Passage soon. Very few of the Convoy have lost Company there being now 97 sail

in sight.

Inclosed is the State of His Majesty’s Ship Marlborough, the Lynn and Hornett

bring up the Rear of the Convoy, which prevents my getting their accounts.

I shall this morning part Company with Commodore Stevens and the India Ships as

they must Steer more to the Southward than our Convoy lays.

etc, Thos Cotes.

Marlborough in Passage

8th May 1757.

In my last letter of the 8th of April by way of Madeira I acquainted

you of my parting Company with Commodore Stevens and the East India Ships. The

10th of April I made the Signal for all Masters of Merchant Ships,

and finding only six light Ships bound to Barbados, and sixty to the other

Islands, I ordered the Lynn to see them safe to Barbados, and with the

remaining Sixty steered for Antigua, where I arrived the 5th Instant,

with all the Convoy. The Store ships went into English harbour and the Merchant

Ships to their different Ports. I delivered Rear Admiral Frankland his

Commission after he had taken the Oaths, and Subscribed the Test, a Certificate

of which is Inclosed, I also told him he must direct his agent in London to pay the Fees of the Office.

The 6th I ran? The Ships bound to Montserrat, Nevis and St

Christopher to their several Ports, and anchored in this Road to get a Supply

of Water and Rum for the Ship’s Company, all the Wine we brought out of England

being expended by the Length of our Passage, I have been obliged to hire a

Sloop to fetch my Water, as old Road is by no means a proper Place for so large

a Ship to lay and there is no Water here, the Moment she returns I shall

proceed with the Trade bound to Jamaica. The Storeships that stopped at Antigua

have some of His Majesty’s Stores on board for Jamaica. I have ordered Capt

Kirke to call at Antigua to convoy them to Jamaica, and I have desired Adml

Frankland to assist in unloading them that the Lynnn may not be detained there.

The Recruits of Colonel Ross’s Regiment I sent to the Head Quarters in a

Schooner W Frankland lent me, four of them dyed in the Passage of Fevers. The

Packetts for Barbados I sent by Capt Kirke, and those for Antigua I delivered

to Admiral Frankland.

Inclosed is an Affidavit, that was yesterday made before the Lieutenant

Governor of this Island, the Person who made it seemed to me to be very

positive as to the facts. I therefore thought it my duty to get an Original to

lay before their Lordships.

Inclosed it the State of His Majesty’s Ship the Marlborough and Hornett Sloop.

I am etc.

Edinburgh Port Royal Jamaica

7 May 1757 659

Recd 22 June,

Read ditto

Sir,

Since my last to you of the 24th March, by his Majesty's Ship the

Biddeford, I beg leave to Acquaint you, for the Information of the Rt

Honourable the Lords, Commissioners of the Admiralty, that his Majesty's Ships

Augusta, Princess Mary and Humber, Arrived here on the 7th of last

month, from the North sides of Hispaniola, Captain Craven Acquaints me in his

Letter of the same day, of his looking into Cape Francois, a Copy of which

Letter I have hereby enclosed. His Majesty's Dreadnought, and Shoreham are

likewise Arrived, from the South sides of Hispaniola.

I have here inclosed you a Deposition of one Joseph Thurston, Master of the

Snow Defiance, giving an Account of his falling in with a Fleet of Ships, Off

the Island of Mona, and one of the Ships carrying a White Flagg at the

Foretopmast head. As in my former Letter to you, Sir, of the 24th of

March, I acquainted you, the French Prisoners, that were taken by one of our

Privateers, gave an account of fourteen Sail of French Men of War, Sailing from

Brest, And as this Master says he saw these ships off St. Domingo, I

immediately dispatched a small schooner up to Port Louis, to look into that

harbour, for if they were the French Squadron, they might have put in there,

but upon her return, the Officer I sent in the Schooner, Informed me, he saw

nothing in the Harbour, but two small Vessels; I therefore Imagine the Fleet

was the Spanish Flota, which is expected every day but as I shall endeavour to

gain the best intelligence I can. I have ordered his Majesty's Ship Lively, who

arrived here with the Roebuck and Assistance, with the Trade from ?? on the 25th

of last month to prepare for the Seas, and propose as she goes well, to send

her up to look into Cape Francois, that I may know if there are any other French

Squadron there, except that of Monsieur Beaufremond, and especially as there is

some reason to think that the French Squadron that was upon the Coast of Guinea

is Arrived there as their Lordships will please to Observe by Captains Wyatts

letter to me of this 25th April.

I have ordered his Majesty's Ship Assistance to Carreen, without loss of time,

and I am ordering to put the Squadron in the best condition I can, having

Stores of any kind, and hope to have some further ?? with the Trade from England, by the time the Squadron is ready for the Sea.

The several Rumours We have had, both from the Dutch and Spaniards, of the

French intending an attack on this Island, has occasioned the Lieutenant

Governor to declare Martial Law, and they are now putting the Fortifications of

this Island into the best postures of Defence they can; I have given them all

the Assistance in my power, by mounting their Cannon and repairing such of

their Carriages as were gone to decay, and shall contine my Assistances to

them, to this Utmost, and hope in a little time to see their Forts in a

suitable situation to repulse any Attack that may be made on this Island.

I would further Acquaint you; for their Lordships Information, that Monsieur

Bart, the new Governor of Hispaniola, has sent a Flagg of Truce, which Arrived

here the 30th of March, to Mr Moore, the Lieutenant Governor, to

prepare an Exchange of Prisoners, by which Opportunity I received a Letter from

Captain Roddan, with an Account of the taking of His Majesty's Ship Greenwich,

a Copy of which I herewith Inclose.

His Majesty's Ship the Wager

is likewise returned to this Port, but am very sorry to Acquaint you of the

Death of Captain Preston, and the Surgeon and Purser of that Ship, I have

appointed Mr Shurmer, first Lieutenant of the Edinburgh, Captain of the Wager,

and Mr Burnett, Midshipman on board His Majesty's Ship Dreadnought, to be third

Lieutenant of the Humber, having moved Mr Dumaresque, first Lieutenant of that

Ship, to be fourth Lieutenant of the Edinburgh, Whom I hope their Lordships

will favour me so far as to Confirm.

I have Inclosed you, Sir, a certain Account of the eight ?? ships that are

Arrived at Cape Francois, under the Command of Monsieur Beaufremond, And

likewise Captain Moore's Account of the Spanish Ships now laying at the

Havanna.

I beg leave to Acknowledge this Receipt of their Lordships Orders of the 3rd

January 1757, relating to ?? the time of the Departure of the first and second

Convoy, for proceeding to England with the Trade if this Island, which I shall

punctually Confirm to, and give the proper Notice thereof.

Captain Weller having Acquainting me, he had appointed Mr John Henry third

Lieutenant of His Majesty's Ship Assistance on the Coast of Guinea, in the room

of one of the Lieutenants who dyed there, And Mr Henry not having passed for a

Lieutenant, Applies to me for an Order of that purpose, which I Granted, and I

Inclose you a Copy of the Certificate of his having passed, together with the

State and Condition of his Majesty's Squadron under my Command.

I am Sir, Your Most Humble Servant,

Geo Townshend

PS

Sir, since writing the above, Captain Wickham of His

Majesty's Ship Augusta, & Captain Forest of His Majesty's Ship Rye having

acquainted me they are desirous of Exchanging their Commissions, I have

consented to it.

Also short list of:

Spanish Ships in Havanna,

French ships at Cape Francois (Haiti),

The English Squadron at Port Royal.

By Alan Baxter and Associates

(Included as it was the residence of Richard Maitland, the progenitor of the

Jamaican Family)

1 The beginnings

The remains of a guard tower suggest that The Highway, on

the higher ground above the flood-prone area to the south, formed a main

approach to Roman London from the east, but it seems unlikely that there was

any significant settlement in the area up until the 16th century. The name

‘Shadewell’ was recorded as early as 1223, and could have derived from Shady

(or Poisoned) Well, Shallow Well, or perhaps a corruption of St Chad’s Well. Despite such early records, the area was sparsely inhabited, and in Tudor

times it was covered with ditches feeding a tidal mill.

Shadwell developed as a notable settlement from around 1600. It was in this

year that it was first mentioned in the baptism registers of St Dunstan’s,

Stepney, and its rapid growth is shown by its frequent recurrence in the

registers thereafter. Its position was ideal for further growth, as Ratcliff

immediately to the east was the nearest landfall downriver of London with a

good road to the capital, and was a place of embarkation and disembarkation for

travellers and sailors alike.

The majority of the land in Shadwell, from the site of the present Church in

the west to the borders of Ratcliff in the east, and from the line later marked

by Cable Street to the river, was owned by the Deans of St Paul’s, who were

inactive landlords. Nevertheless, in the early 17th century there was a

considerable growth in marine industries and trades in the area, which caused a

great increase in population and led to a house building boom. Over 60 fines

were levied on Shadwell houses built illegally in the 1620s and 1630s along The

Highway and the riverfront, and beside Fox’s Lane which ran between them just

east of where the present Church now stands.

By the time the Commonwealth government surveyed the Dean’s lands in 1650 there

were 703 houses in Shadwell, excluding the area west of Fox’s Lane not owned by

the Dean. Around 60% of the householders made their living on the river, as mariners

or watermen etc, while another 20% were in trades reliant directly on shipping,

such as shipbuilding or supporting crafts. 32 wharves lined the 400 yards of

riverfront, while roperies, timber yards and smithies filled much of the land

behind.

In a few decades Shadwell had developed piecemeal into a considerable

settlement through speculative building, which had created a sprawl of houses

and industries with no defined centre and little social organisation. At around

3% of the population, the ‘middle class’ in Shadwell was extremely small in

comparison to the other Stepney hamlets. As late as 1640, the parish of Stepney

had 41 officers, but there were none responsible for Shadwell. The area

desperately needed social leadership and physical improvement.

2 Thomas Neal and urban development

Thomas Neal (or Neale) was a speculative builder,

responsible for Neal Street and the Seven Dials area of the West End. In 1656

he built a chapel in Shadwell (described in 3 below), fulfilling the wishes of

many local residents who felt that, with a population of around 6,000 people,

the area needed a focal point for the community. His activity in Shadwell

brought him into close friendship with William Sancroft, the Dean of St Paul’s

who had recovered the land after the Restoration, and who later became

Archbishop of Canterbury. This close relationship allowed Neal to obtain the

lease of Shadwell on extremely favourable terms in 1669, and he set about

improving the area in the hope of increasing its value.

One of Neal’s first successes was in 1670, when his influential friends allowed

him to overcome numerous objections to splitting up the huge parish of Stepney.

In spite of other previous and much more practical proposals for four equal

parishes to be created, he gained separate parish status for the Shadwell

Chapel. The new parish church, serving an area only 910 by 760 yards, was

rededicated to St Paul in honour of the Dean of St Paul’s who had been so

favourable toward him. This victory gave Shadwell its own social structure

centred around the parish church, with its own organisation of churchwardens to

look after the community, ensure law and order, and levy rates to fund local

improvements.

Neal’s commitment to the area continued until his death at the end of the

century. In 1673 he rebuilt over 100 homes after they were destroyed by fire,

replanning the area with wider streets and building a new quay along the river.

In 1682 he rehoused over 1500 families after a massive fire in Wapping and

Shadwell, laying out Dean Street as a new thoroughfare. Neal also obtained a

charter to hold a market, which he built in 1681-82, so that his tenants did

not have to travel to the City to buy and sell, the nearer Ratcliff market

having foundered. In 1684, he opened a water works that pumped water from the

river to houses from East Smithfield to Stepney, and lasted until it was bought

up by the London Dock Company in the early 19th century.

Thomas Neal’s achievement was to turn the ramshackle, amorphous grouping of

houses into a real community with a religious and social centre in its parish

church, and a commercial heart surrounding its market. He greatly improved the

attractiveness of the area, paving the way for it to become famous as a

residence of sea captains during the 18th century.

3 The first church

The Chapel was built between 1656 and 1658 on land just

outside the Dean of St Paul’s estate, along The Highway on the high ground that

never flooded. It was a relatively simple building, still owing much to the

medieval past in its triple-gabled nave and aisles layout, though the

individual features such as the round-headed windows were classical.

Some important elements of this original Church still survive in the present

building, most notably the font. The pulpit was thought to be original by some

historians, but a different type is shown on illustrations of the old interior.

There also remain considerable items of furniture and plate from the old

Church.

4 The eighteenth century

Shadwell continued to grow in the early part of the 18th

century as most of the spare land was developed. A survey in 1732 noted over

1800 houses in the parish, many of which had degenerated into slums. Unskilled

people flocked to the parish from as far afield as north east England and Ireland, looking for casual labour on the docks and wharves. The continuing increase in

seaborne trade and naval expansion contributed to a growth in marine

industries, including the roperies with their typical long, narrow sheds and

walks, so evident on early maps.

Shadwell was famous for its many master mariners; over 175 were registered as

living in the parish at one time or another. By the end of the century, St Paul’s was known as ‘the Church of the Sea Captains’, and 75 were said to be buried in

its vaults. Captain Cook was perhaps the most famous parishioner, though Thomas

Jefferson’s mother was also a regular worshipper before emigrating to America. The Church was the centre of community life in Shadwell, and attracted

considerable bequests for its charitable works. Although not one of the more

missionary churches in the area, it was nonetheless the scene for five of John

Wesley’s sermons between 1770 and 1790, including his very last.

Shadwell’s maritime connections opened it up to the successive waves of

immigrants that came to Britain from the later 17th century. Huguenots were

among the first to arrive, and planted the ancient mulberry tree which still

survives in the Rectory garden for their silkworms. Spanish and Portuguese Jews

arrived later, and were known for their skills in metal working and casting.

Germans and Scandinavians were also a strong presence in Shadwell, being mainly

concerned with the timber trade and related businesses. The area was also

notorious for its many taverns and brothels, which did extremely well out of

the sailors passing almost continuously through the area.

The industrialisation of the area slowly led to a decline in the social status

of the inhabitants, and in their living conditions. J P Malcolm described

Shadwell in the following terms in 1803:

Thousands of useful tradesmen, artisans and mechanics, and numerous watermen

inhabit Shadwell, but their homes and workshops will not bear description; nor

are the streets, courts, lanes and alleys by any means inviting. …[the Church]

is a most disgraceful building of brick totally unworthy of description.

The fabric of the Church suffered from the inability of the parishioners to pay

adequately for its upkeep. The unstable south wall was rebuilt in 1735, but by

the end of the century the local people could not raise enough money to perform

vital repairs. When part of the ceiling fell down in 1811, the Church was

declared unfit for use, and was closed for all services except christenings and

burials.

5 The second church

With their Church in ruins, the relatively poor congregation

had little chance of rebuilding it by themselves. A further hindrance was the

opposition of some major local ratepayers, most notably the London Dock

Company, to the added expense. In 1817, the parishioners finally succeeded in

securing a special Act of Parliament to authorise rebuilding; the Act’s wording

recognised that although the population of the parish was estimated at 10,000,

they were not very wealthy, ‘the far greater part of them being labourers in

the docks and on the River’. The architect chosen was John Walters, whose

estimate for the new Church came to £14,000. The sale of the fittings and

materials from the old building before demolition fetched only £223. 13s. 0d.

and £419. 1s. 8d., respectively, leaving the local people with a considerable

struggle to find the remainder.

Tradition maintains that the parish obtained a grant from the Church Building

Commission to cover the cost of the new building. The Commission was established

by Act of Parliament in 1818, to spend £1,000,000 in providing new Anglican

churches, both as a memorial and thanksgiving for the victory at Waterloo, and

‘lest a godless people might also be a revolutionary people’. Another Act added

£500,000 to this in 1824. There is no reference to St Paul, Shadwell receiving

a grant from the Commission in M.H. Port’s comprehensive study, but one seems

to have been made nevertheless. In the event, the building cost £27,000,

ranking it as one of the more expensive of the time.

John Walters

John Walters was born in 1782, and learned his architecture

under D. A. Alexander, the designer of the famously Piranesian Maidstone Gaol,

most of what is now the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, and numerous

dock and warehouse buildings in Wapping and elsewhere. Walters lived and

practised in Fenchurch Buildings in the City, and was by all accounts a

diligent, able and respected architect, with an almost fanatical interest in

his vocation. As well as several buildings, he also had an interest in naval

architecture and designed a diagonal truss to strengthen ships’ hulls. Walters

died in 1821 at the age of 39, the result of chronic overwork. He left a widow

and a son, Edward (1808-72), who became a successful Manchester architect.

Walters’ first notable building appears to have been the Auction Mart in Bartholomew Lane, a fine design which was completed in 1809. Its exterior was rather

Palladian, while the interiors were inspired by Sir John Soane’s Bank of

England. St Paul’s Shadwell (1819-20) was also in a classical manner, though

this time leaning much more towards the Greek influences of Neoclassicism. The

Gothic of St Philip’s Chapel, Turner Street, Stepney (1818-20) was impressive

for its time, although by the standards of later Victorian architects its

detailing appears clumsy. This last building is very different to Walters’

usual style, and in fact was probably mostly designed by his pupil Francis

Goodwin, who had was a very prolific designer of Gothic churches for the Church

Building Commission (see M. H. Port, pp. 71-72). All of the other buildings

known to have been designed by John Walters have now been demolished. St Paul’s, Shadwell therefore possesses particular interest as his only surviving building.

With the money in place to pay for the new Church, Walters’ design was executed

by J. Streather, as recorded on the west front. The building consisted of a

central box-like main space with a projecting chancel at the east end, and a

tower at the west end flanked by staircases to the galleries, and included a

large crypt which extended under the entire Church and also eastwards and

westwards under the Churchyard. The building was largely constructed out of

yellow brick, with a stone plinth, and dressings of stone and stucco render,

giving an appearance described by the Gentleman’s Magazine as ‘simply neat, and

elegantly chaste’. It was apparently consecrated on 5 April 1820, although some

sources give the year as 1821. The railings around the edge of the Churchyard

appear to date from the early 19th century and were probably designed along

with the Church itself.

Exterior

The Church is like a rectangular box with roughly equal projections at the east

and west ends, which contain the tower and stairs, and chancel, respectively.

The central box contains the main body of the Church, and is astylar, whereas

the two projections are decorated by pilasters, with a pediment at the west

end. The windows are also subtly different, with those on the upper part of the

main body having individual cornices above their architraves, whereas those on

the projections have plain architraves. Such minor details show the

thoughtfulness of Walters as an architect.

The western projection of the Church has stone steps with metal railings leading

to central panelled double doors flanked by round-headed niches, set in a

tetra-style Tuscan pilaster portico supporting a triangular pediment, above

which sits the base of the tower. Three tablets above the door and niches

record the rebuilding of the Church and the names of Walters as architect and

Streather as builder. The sides of this projection act as the flanks of the

temple portico, with pilasters at the north and south corners and two

rectangular windows one above the other. Where the flanks meet the main body of

the Church are interesting gargoyles at cornice level, much decayed now but

just discernible as fish or stylised dolphins, alluding to the Church’s

maritime connections.

The steeple rises through several stages from its square base above the

pediment, moving from a square lantern with four pairs of corner columns

supporting an engaged entablature, to a circular tempietto surmounted by

inverted brackets supporting an obelisk. Bridget Cherry notes accurately that

‘The stone steeple evokes Wren’s St Mary-le-Bow via Dance’s St Leonard

Shoreditch’. The Gentleman’s Magazine described it as ‘peculiarly beautiful,

and it is not too much to say, that in correctness of design, and in the simple

harmony of its several parts, it scarcely yields to the most admired object of

the kind in the metropolis’. Within it hang eight bells, six of which were

recast from the peal of the original Church. The clock and its three

clock-faces underneath the lantern would The south and north sides of the

central box of the Church are virtually identical. They have two rows of five

rectangular windows lighting the ground floor and the galleries. The lower

windows rest directly on a stone string course, and both rows are set within

stone architraves, which have now been painted white. Each side is capped by a

plain rendered frieze and cornice, at the same height as that on the west

portico, with a the eastern projection is also decorated with Tuscan pilasters,

with another tetra-style portico framing the rear outer wall of the chancel,

this time without a pediment. The centre originally featured a door at ground

level, with a blank wall above (perhaps originally decorated with a

commemorative tablet), though in 1848 William Butterfield blocked up the door

and inserted a tripartite round-arched window into the upper part of the wall

(see 8 below). Either side of the central bay are niches with tablets above,